Recently, a relatively fruitless research trip took me around a couple of new-to-me museums. In the course of my perambulations, I came across several visually arresting pieces that have a bearing on the discussions we’ve had here on Tor.com, about historically authentic sexism and cop-out arguments.

So this week, I thought I’d present some visual arguments for the historical validity of many ways of representing many different sorts of women, from Hellenistic Greece to seventeenth-century France.

The photo quality is decidedly amateur. And the naked female wrestlers may or may not be work safe.

First, let’s look at a marble from late 4th century BC Attica, in Greece. Here we have a female slave (definitely a servant, free or unfree) in a posture of mourning. This marble was one of a pair, part of an elaborate funerary monument—for an elite man, needless to say—but still, we have a depiction of a lower-class woman, however tailored to upper-class mores it may be.

(Inscriptional evidence attests that a number of sculptors in Classical and Hellenistic Greece were themselves unfree.)

Our second image comes from Egypt. A funerary portrait on wood, painted sometime during the 2nd century CE, it depicts a young woman of prosperous standing, as witness her gold jewellery and earrings.

Let’s skip past the medieval period (shockingly, I’m not really geeky for the Middle Ages: too much religious art) to the Renaissance in Northern Europe, with St. Wilgefortis, known in Germany as St. Kümmernis, a mythical saint from the Iberian peninsula who took a vow of virginity, prayed to be made repulsive to escape a dreaded marriage, and whose father crucified her as a result.

This image of the saint—whose cult was debunked in the late 16th century—comes from Osnabrueck around 1540. She looks suspiciously cheerful for a woman who’s nailed to a cross, but I suppose that’s religion for you. (Or maybe it’s just Gothic art.)

I don’t know much about Eleonora of Toledo, Duchess of Florence and Tuscany (1522-1562) but what I do know is fascinating. A noblewoman of Spain with Castilian royalty in her ancestry, she married into the de’Medici family when they were still new to their ducal honours, and had a high public profile in Florence, as well as serving as regent while her husband was away.

This portrait was painted sometime during the final two years of her life, when she was suffering severely. She doesn’t look terribly happy (and I suspect my terrible photography doesn’t improve the matter one whit), but she does look impressive. And also rather In Charge, to my eyes.

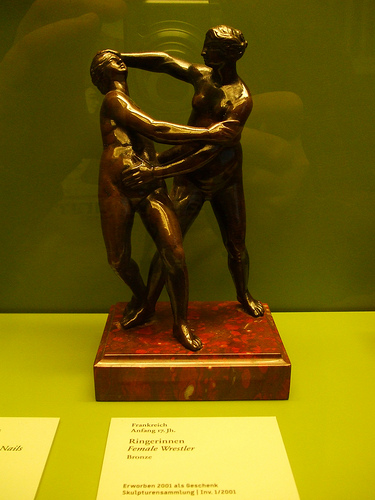

Finally, I’d like to draw your attention to a piece of art that took me rather aback when I walked past it. A bronze from 17th century France, it depicts two nude, grappling female wrestlers. The erotic undertones are fairly clear, I think, but so is the musculature and the plausibility of the wrestling pose.

We talk a lot, and write a lot, about the roles and representations of women. It is also written: “A picture is worth a thousand words.” Here is a small amount of visual evidence for the diversity of representations of women in history: let’s do just as well, or better, in speculative fiction.

Find Liz Bourke on Twitter @hawkwing_lb.

I wonder if the representations of women in the visual arts like painting and sculpting is greater both in numerical terms and in status (more principal positions, more favorable depictions) than corresponding representations in literary arts. In other words, are women “seen but not heard”? And, if so, what accounts for the difference? It would seem to date back a long way, given the various “Venus” sculptures of the Paleolithic periods.

… and now i know the reason i come to tor.com is for wheel of time stuff only.

besides the religion bashing, i completely disagree with your “erotic undertones clear” comment … not sure how you interpret that to be erotic… but by just looking at the photo. i do not.

In a lot of representations, St. Wilgefortis (also known as St. Uncumber) is depicted with a beard, which grew in miraculously in order to put off her husband-to-be.

Eugene R. @1:

An interesting question. Although the prehistoric plastic arts are open to multiple valences of interpretation – see some of the scholarship on “goddesses with upraised arms” and Cypriot Neolithic figurines in the Aegean, for example.

CorDarei @2:

I’m not sure how you get to “religion-bashing” from a statement of my absence of geekery over medieval religous art – but okay, tiger. Thanks for dropping in dismissively!

It’s cool that you don’t find the naked wrestlers to have erotic undertones. Extrapolating from historical attitudes to female atheletes, however, I’m reasonably convinced that in its original context it was designed, or expected, to have a titillating effect.

(I find it erotic. But then, I think representations of people – naked or not – involved in certain kinds of exercise to be pretty hot.)

Raskos @3:

I know! I think that’s both a) a weird and b) a pretty cool saintly superpower.

Here’s a couple of articles that are psuedo related, inc the first portrait of a person…who happened to be a woman. Touches upon @1

http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/2013/jan/24/ice-age-art-british-museum

http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/feb/05/ice-age-art-jonathan-jones

no… it was the “but I supose that’s religion for you” comment that felt like a bash. Reading that wiki was kind of interesting that the original piece was supposed to be Jesus, and not a woman.

Also, wouldn’t being from France be an indicator that nudity doesn’t necessarily = erotic?

Today of all days it’s rather hypocritical to be whinging about (supposed) religion bashing. Sigh.

Specially in light of the fact that comment reflects religion as the opiate of the people, and the typical depictions of euporia/estaticism.

CorDarei @6, A Fox @7:

Almost every premodern religious depiction of a crucifixion I’ve ever seen – and I’ve seen a good few – seems to have an unusual amount of happiness in the facial expression for someone who’s undergoing death by torture. I’ve nothing particularly against the idea of transformation through suffering, but it does crop up uncomfortably (for me) often in certain religious settings.

CorDarei, can you unpack your thinking there for me a bit?

I wouldn’t want to meet that Duchess of Florence–she looks like a pretty nasty customer. On the other hand, the woman in the funerary painting looks like someone you could share a comfortable chat with. Amazing how artists can speak to us across the centuries.

How about a picture of my favorite saint, Saint Brigit of Kildare (who also bears a remarkable resemblence to the ancient Celtic goddess Bridgid)? One of her miracles was changing water into beer. At the risk of being sacrilegious, to my mind this was a more admirable feat than turning it into wine!

One point to consider in our discussion is that there is a long tradition of both religious and philosophical approaches to dealing with the matter of suffering, an inescapable reality of life for almost all human existence (and not entirely absent even lately). Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy was the most copied book in Europe for a millenium after it was published in 524 CE, for example.

While some of those traditions do attempt a sort of “ju-jitsu” approach (Suffering is ennobling!), many of them merely attempt to address the better ways to response to the approach of suffering, mainly through distraction (contemplate Higher Things, like Art!) or diminution of response (do not whine!). Since these approaches often dovetail (a Stoic being unmoved by suffering looks a lot like a Christian humbly accepting God’s trials), it may be a bit hard for us to determine to what tradition a piece of Art is allied without some external information as to the artist’s or the subject’s beliefs.

AlanBrown (@9): I thought that Eleanora of Toledo looked rather sad but not necessarily mean; she seems to have a lot of things on her mind, her illness being one of them. I would not want to bother her and waste her time on any trivial matter, certainly! And it is nice how, whatever the tradition, the transformation of water into an alcoholic form (of whatever variety) is accepted as a miracle. Works for me!

“Here is a small amount of visual evidence for the diversity of representations of women in history: let’s do just as well, or better, in speculative fiction.”

— we don’t? Given the time-spans involved, of course.

It’s very easy to use historical images, especially unaccompanied visual ones, as a blank sheet onto which to read your own interests.

The most common is to project modern stylistic/aesthetic preoccupations onto the creators, as if they had been making stuff intended to be put in museums or hung in art galleries, like a modern painting.

Interpreting them as “originally intended”, on the other hand, is -hard-, even more so than with the Constitution (glyph of irony).

That involves recreating the context.

Eg., Athenian depictions of Athena (and the ubiquity of the image) could, if we didn’t have written records from the period, be easily read in extremely misleading ways. (I did an essay in my student days in which an archaeologist in an alternate universe where only the physical remains of Ancient Greece remain “proves” that Athens was an amazonian matriarchy.)

The essential point of the Wilgefortis story, for example, (and it’s a very common theme in early Christian iconography, there were a lot of virgin-martyr saints) is a deep fear and hatred of sexuality (particularly female sexuality) as contaminating and “icky”, and a hatred of the material world itself, a longing to transcend and escape from it.

The theme is even more overt in the Gnostic literature but it’s powerful in that period’s Christianity too.

Incidentally the captcha feature here is a pain in the arse; it took me six tries to get by it.

I do love to see historical images of women! My PhD thesis was on the representations of Roman imperial women, and it was a huge difference to look at the way that the wives and daughters (and mothers) of Emperors were represented on statues and coins as opposed to how they were described in the literature – where it assumed everybody KNEW they were all evil harridans.

The statues, coins etc were distributed during the lifetimes of those women, while the literary sources were often written hundreds of years later, under different regimes, and yet I struggled in my department to convey the importance of the non-written source material.

This is one of my favourites –

– a Roman lady writing. It has at various times been interpreted as Sappho (cos no other woman in the history of the world wrote anything), as a poet, and as a housewife doing her shopping list… all of which are massive assumptions, but at least it’s one in the eye for all the academics who believed with straight faces that women probably didn’t write at all in Ancient Rome, and *that’s* why so many of the historical sources we have are by men.

– a Roman lady writing. It has at various times been interpreted as Sappho (cos no other woman in the history of the world wrote anything), as a poet, and as a housewife doing her shopping list… all of which are massive assumptions, but at least it’s one in the eye for all the academics who believed with straight faces that women probably didn’t write at all in Ancient Rome, and *that’s* why so many of the historical sources we have are by men.

TansyRR @12:

Yes indeed! Have you read Ellen Greene’s edited volume on women poets in Greece and Rome? (BMCR review.) I’ve been eyeing it longingly, but I have so much else to read first.

The Roman imperial period and its iconography obviously isn’t my speciality, but I’ve always had a soft spot for Julia Maesa and her female relatives…

@13. hawkwing-lb

No I hadn’t heard of that book – thanks, it sounds interesting! Julia Maesa and the other scary Severan ladies are favourites of mine too.

There’s another great bronze of a Spartan girl running (only partial nudity though):

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/gr/b/bronze_figure_of_a_girl.aspx

The Ellen Greene book sounds fantastic! I’ve been looking for Erinna’s poetry for a few years, and it is not easy to find.

erythrina @15:

It’s pretty hard to find a good edition of any of the female poets bar Sappho, isn’t it?

“… not sure how you interpret that to be erotic…”

Because of all the possibilities that the artist could have gone with, this is what we get. This is where the wrestler’s hands are placed, how their legs are intertwined, this is how much we can see of the their bodies, etc.

It’s very much NOT erotic in the manner of glossy, sexualized objectification but, personally, I think that’s what makes it so erotic. It’s emphasizing the real sensualness of what is going on, rather than trying to creating something fake. And the way that the women are acknowledged as people also makes it’s easier for me to place myself in the wrestler’s (lack of) shoes and imagine my body in that position, touching someone like that, being touched like that. And to me that’s a thousand times more erotic than most of the sexualized and therefore supposedly erotic images that are so often used in advertising, etc.

(I also love how you can see the reflection of Liz and her camera in that photo. Something about the way it’s all framed makes it look like a statement rather than accidental.)

TansyRR – that sounds like a really cool topic!

jennygadget @17:

Pure serendipity, I’m afraid.

Serendipity is the source of some of the best art and science!